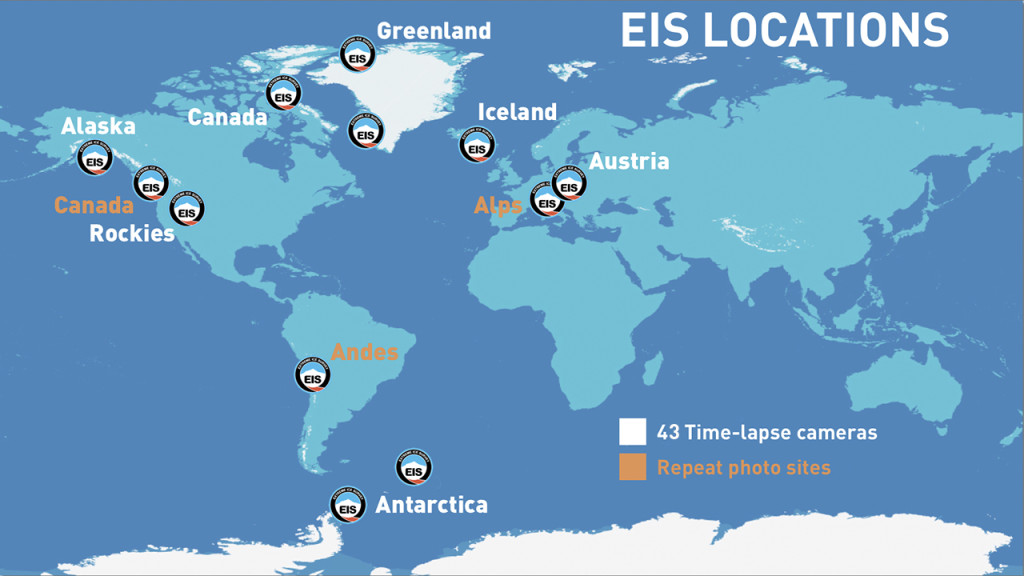

Extreme Ice Survey Camera Locations

How did the Extreme Ice Survey get started?

In 2005, internationally acclaimed nature photojournalist James Balog traveled to Iceland to photograph glaciers for The New Yorker. This led to a 2006 National Geographic assignment to document changing glaciers in various parts of the world. In the course of shooting that story (which became the June 2007 cover story, “The Big Thaw”), Balog, who in addition to being a photographer is a mountaineer with a graduate degree in geomorphology, recognized that extraordinary amounts of ice were vanishing with shocking speed. Features that took centuries to develop were being destroyed in just a few years or even just a few weeks. These changes are the most visually dramatic and immediate manifestations of climate change on our planet today.

In 2005, internationally acclaimed nature photojournalist James Balog traveled to Iceland to photograph glaciers for The New Yorker. This led to a 2006 National Geographic assignment to document changing glaciers in various parts of the world. In the course of shooting that story (which became the June 2007 cover story, “The Big Thaw”), Balog, who in addition to being a photographer is a mountaineer with a graduate degree in geomorphology, recognized that extraordinary amounts of ice were vanishing with shocking speed. Features that took centuries to develop were being destroyed in just a few years or even just a few weeks. These changes are the most visually dramatic and immediate manifestations of climate change on our planet today.

Why does EIS exist?

Seeing is believing. Real-world visual evidence has a unique ability to convey the reality and immediacy of global warming to a worldwide audience. The Extreme Ice Survey provides scientists with basic and vitally important information on the mechanics of glacial melting and educates the public with firsthand evidence of how rapidly the Earth’s climate is changing. EIS is a voice for landscapes that would have no voice unless we gave them one.

Seeing is believing. Real-world visual evidence has a unique ability to convey the reality and immediacy of global warming to a worldwide audience. The Extreme Ice Survey provides scientists with basic and vitally important information on the mechanics of glacial melting and educates the public with firsthand evidence of how rapidly the Earth’s climate is changing. EIS is a voice for landscapes that would have no voice unless we gave them one.

How does EIS do it?

Guided by the recommendations of glaciologists, in 2007 the EIS team installed its time-lapse cameras at sites that represent regional conditions and have high scientific value. Typically these cameras are anchored on cliff faces above the glaciers. It took six months of experimenting to come up with a camera system sturdy and reliable enough for our purposes. We use Nikon D200 digital single-lens reflex cameras powered by a custom-made combination of solar panels, batteries and other electronics. The cameras are protected by waterproof and dustproof Pelican cases, mounted on Bogen tripod heads, and secured against arctic and alpine winds by a complex system of anchors and guy wires. Each unit weighs more than 100 pounds. Solar panels collect power that is stored in batteries; customized controllers trigger the cameras only when there is sufficient light. Downloads of digital images occur as frequently as every few months or as rarely as once a year, depending on how remote a site might be, and our timelapse videos are updated with new images.

Guided by the recommendations of glaciologists, in 2007 the EIS team installed its time-lapse cameras at sites that represent regional conditions and have high scientific value. Typically these cameras are anchored on cliff faces above the glaciers. It took six months of experimenting to come up with a camera system sturdy and reliable enough for our purposes. We use Nikon D200 digital single-lens reflex cameras powered by a custom-made combination of solar panels, batteries and other electronics. The cameras are protected by waterproof and dustproof Pelican cases, mounted on Bogen tripod heads, and secured against arctic and alpine winds by a complex system of anchors and guy wires. Each unit weighs more than 100 pounds. Solar panels collect power that is stored in batteries; customized controllers trigger the cameras only when there is sufficient light. Downloads of digital images occur as frequently as every few months or as rarely as once a year, depending on how remote a site might be, and our timelapse videos are updated with new images.

What is extreme about EIS?

Everything! The scope of the project, the challenging logistics, the fierce weather conditions, the forbidding terrain, and the prodigious distances (more than 6,000 miles from the remote camera at Umiamako Glacier in Greenland to the repeat photography site at Chacaltaya, Bolivia). EIS expedition teams service cameras that are as far as 80 miles from the nearest village, in conditions that can quickly turn from dangerous to deadly. The teams reach the cameras on foot and on horseback, by dog sled and skis, from fishing boats and helicopters that cost up to $8,500 an hour to charter. Extreme, indeed—and worth it! Already our cameras have captured the only known images of landscapes that no longer exist.

Everything! The scope of the project, the challenging logistics, the fierce weather conditions, the forbidding terrain, and the prodigious distances (more than 6,000 miles from the remote camera at Umiamako Glacier in Greenland to the repeat photography site at Chacaltaya, Bolivia). EIS expedition teams service cameras that are as far as 80 miles from the nearest village, in conditions that can quickly turn from dangerous to deadly. The teams reach the cameras on foot and on horseback, by dog sled and skis, from fishing boats and helicopters that cost up to $8,500 an hour to charter. Extreme, indeed—and worth it! Already our cameras have captured the only known images of landscapes that no longer exist.

Who is on the EIS team?

The project is a collaboration among imagemakers, engineers, and scientists, all devoted to documenting the changes transforming arctic and alpine landscapes today. In the Extreme Ice Survey, art meets science. EIS celebrates the otherworldly beauty of ice-cloaked landscapes while providing scientists with crucial data on the speed and extent of glacial retreat. Our President, James Balog, collaborates with scientific partners including Dr. Jason Box and Dr. Tad Pfeffer of the Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research at the University of Colorado.

The project is a collaboration among imagemakers, engineers, and scientists, all devoted to documenting the changes transforming arctic and alpine landscapes today. In the Extreme Ice Survey, art meets science. EIS celebrates the otherworldly beauty of ice-cloaked landscapes while providing scientists with crucial data on the speed and extent of glacial retreat. Our President, James Balog, collaborates with scientific partners including Dr. Jason Box and Dr. Tad Pfeffer of the Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research at the University of Colorado.

How long do you plan to continue the Extreme Ice Survey? Are you planning to expand the project to other areas?

EIS is a program of the Earth Vision Institute, which relies on donations from supporters of our work. We will absolutely continue to capture images around the clock from approximately 43 cameras worldwide. We are also leveraging insights gained from the EIS to document other aspects of the planet’s changing ecosystems. Sign up for our e-news to be the first to receive new video footage as it’s released to the public! Learn more about how you can support our field work, with a one-time or ongoing funding partnership with us.